By Troy Gilmore, Assistant Professor, School of Natural Resources

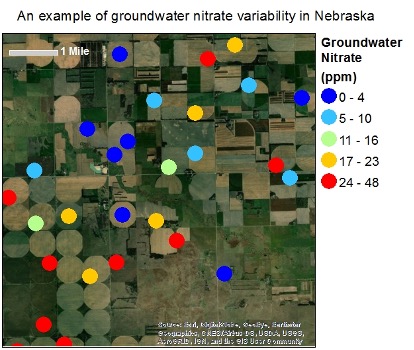

Have you ever wondered why groundwater nitrate maps show so much variation across Nebraska? Or why wells near to your own tested well have such different nitrate levels? The answer has three parts. Nitrate in groundwater varies from place to place because of differences in:

- the amount of nitrate that travels below the root zone and toward the water table;

- the natural processes in the aquifer that remove nitrate from groundwater; and

- the length of time for nitrate to reach wells of a different depth or construction standard.

In the following, we’ll break down those three pieces and explain how they affect nitrate levels.

Nitrate Seeping Underground

Nitrate reaches the deeper unsaturated subsurface regions — below crop root zones, for instance — due to application of fertilizers, mineralization of organic matter, and/or movement of animal or human wastes into the ground. The rate at which this occurs is highly dependent on local soils and the amount and timing of precipitation or applied water in the area. Once nitrate has moved below the root zone, where it can be utilized by plants, nitrate will easily move downward toward the water table and into the groundwater system. Most high-nitrate groundwater (e.g., > 10 ppm) is located near areas with intensive row crop production, although animal agriculture can also contribute. There are cases where nitrate is naturally released from subsurface sediments, but these are relatively rare and localized.

Naturally Breaking Down Nitrate

Since nitrate tends to stay dissolved in water, it moves along with groundwater through the aquifer. Once in the aquifer, nitrate can only be removed in two ways. One way is removal of nitrate-laden groundwater from the aquifer through pumping or through natural seepage into streams or springs. The second way nitrate can be removed is through natural removal processes within sediments. The primary natural process is denitrification, where bacteria in the aquifer sediments consume nitrate. Denitrification only occurs in low-oxygen environments, which does not occur everywhere in the unsaturated layer or groundwater system. In Nebraska, it is possible that groundwater flowing to one well will undergo denitrification and therefore have low nitrate concentration. Meanwhile, a nearby well might receive groundwater that has undergone minimal denitrification and still has high nitrate concentration. Even though these two wells might be located on the same farm, they can have very different nitrate concentrations.

Distance from the Source

Wells that are very shallow and close to a major source of nitrate are viewed as especially vulnerable to high nitrate concentrations. One reason is that nitrate can arrive at the well relatively quickly because it does not have far to travel in the soil profile. In fact, two wells installed atthe same location but at different depths may have very different nitrate concentrations. The shallower well is more likely to have high nitrate, while the deeper well may have low nitrate. This is possible because groundwater, and the nitrate dissolved in it, moves slowly downward below the water table. In many locations groundwater moves only a few inches of feet downward vertically in a given year depending on geology and the rate at which groundwater is being replenished by recharge. So it is not hard to imagine that it could take many years for groundwater nitrate to reach a well installed deep in the aquifer. It is possible that current nitrate maps, these two wells would have very different nitrate concentrations even though they are in close proximity.

An example of groundwater nitrate variability in Nebraska.